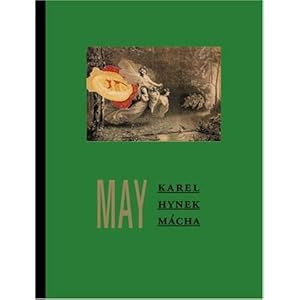

I've just finished reading May by Karel Hynek Mácha, a long narrative poem translated from the Czech by Marcela Sulak and published in a beautiful edition by Twisted Spoon Press. This book is so attractive a physical object, in fact, that you will spend at least as much time gazing at and fondling it as you will reading the text. Be careful, however, not to drool, as this may be injurious both to your social standing and the fabric of the book.

As the very useful introduction explains, the poem, first published in 1836, marked a watershed in Czech letters as it ruptured the absolutism of patriotism and nationalism as dominant themes, and embraced many of the Romantic ideas, themes and techniques which had already pervaded other European literatures and cultures. May also broke new metrical ground, and saw the author introducing the iamb into his country. I can picture the scene now, as Mácha pads around the quieter districts of Prague and the outlying countryside, stealthily crouching to open the door of a small but comfortable cage to usher out another flock of iambs into the wild. Da DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM resound their tiny feet as they scatter abroad, giddy with the excitement of freedom and relishing the prospect of befriending the native dactyls.

Anyhoo - the poem remains massively popular in its native land, with new editions disappearing rapidly from bookshops and schoolchildren being able to recite - presumably before they can be restrained - huge chunks of it verbatim. Learning this made me feel somewhat bereft of a poem with similar status in the home life of our own dear nation; I'm not sure Morte D'Arthur quite passes muster in this capacity, and there doesn't seem to be the same unselfconscious interest in and embracing of poetry nationally and across all classes as there would seem to exist in Slovavakia and (in my experience, for example,) Wales. Discuss.

The poem itself is a rich mixture of melodrama, romanticism and lyricism, and is structured around the last hours and execution of a 'forest lord' who has led a gang of criminals and who has been arrested and convicted for killing the man who ravished his (the forest lord's) lover, this man happening to be his (ditto) father. Meanwhile, his (you know whose) lover languishes and pines by a lake, waiting in vain for her paramour's return. This rather stark framework is decorated with unusual and arresting imagery, particularly of nature, and the poem is particularly good at weaving together natural description with the portrayal of psychological states and ruminations on mortality. There is excellent and dramatic use of repetition and an extraordinary interlude in which the spirits, landscape, flora and fauna of and around the graveyard sing a chorus to explain how they will lay the condemned man to rest:

WASTELAND

"Then I will breathe a pleasant fragrance."

SETTING CLOUD

"I'll sprinkle on the coffin rain."

FALLING FLOWER

"I'll make the wreaths for it."

LIGHT WINDS

"We will take them to the coffin."

FIREFLIES

"Little candles we will bring."

STORM FROM THE DEEP

"I will awake the hollow bells."

There is also a very powerful and moving scene in which the surviving outlaws sit on the ground an intone a dirge for their fallen leader, and the very opening of the poem is evocative and compelling:

It was late evening - first of May -

was evening May - the time for love.

The turtledove invited love

to where the pine grove's fragrance lay.

The silent moss murmured of love,

the flowering tree belied love's woe.

I've enjoyed everything I've read from Twisted Spoon, a publisher as interesting as it sounds, and recommend that you buy their entire list as Christmas presents for your legions of pals.

What date was this poem written?

ReplyDeleteIt was originally published in 1836

ReplyDelete